How to Be a Good People Manager

As a manager you can make people miserable in the workplace. Here’s how to make them happy and productive.

Recently, my team at Facebook was joined by an intern who I’m managing for 12 weeks. As a new manager I had to take a class on how to manage people well.

I was excited to take the class as I’ve been on the receiving end of bad management a few times throughout my career. I had a vague idea of how those situations could have gone better, but I didn’t have a well-defined mental model of what good management was.

A good manager is often the difference between a happy and productive employee who is retained by their company, and one who is miserable and looking for another job. There’s a saying that goes:

“People don’t leave bad companies, they leave bad managers.”

If you’re an effective people manager, you can scale your impact many times over by getting the most out of your reports. As a bonus, you get to improve their daily happiness and fulfillment at work.

The skill of people management is critical to the success of an organization and the welfare of its employees. And yet, it’s often not accompanied by the rigorous study, practice and improvement that people put into other skills.

The Class

The class took the whole day to thoroughly explain the SLII model of leadership and management. After the class, I thought back to the times I had been stung by bad management myself. I realized that all of those times could have been prevented had my manager stuck to this model. I asked my friends about their bad management experiences, and the same was true for them.

The model defines a set of “leadership styles” and “development levels”.

There are four leadership styles, “S1” to “S4”, and four development levels, “D1” to “D4”.

Development Levels

A development level is defined by the skill of your report in a given task, and their commitment to the task. Their commitment to the task is a combination of their confidence in executing the task and their motivation to do it.

D1

Someone is a D1 if they have very little experience in the task they have been assigned. Often D1s are new hires who lack context on the team’s work and processes. Although they may have previous experience somewhere else, they may lack the company-specific knowledge necessary to complete the task. They are very much in the dark. Despite this, a D1 will usually be highly motivated, as they are eager to learn and impress. You can understand what it feels like to be a D1 by thinking back to the first few times you practiced a new skill you wanted to learn.

D2

Someone is a D2 if they have some skill or experience in the task they have been assigned, but not enough to operate independently. A D2 is often someone who was recently a D1 but has had some time to gain more knowledge and experience. They still have a low skill level, but they are often now less motivated as they struggle with getting better. You can understand what it feels like to be a D2 by thinking back to a time when you tried to learn a new skill but struggled to get better at it. This is the period when most people give up.

D3

Someone is a D3 if they have enough skill and experience to operate without instruction. Although they are highly skilled, their commitment to the task fluctuates. They may sometimes lack the confidence to execute, even if they have all the necessary skills. This is often the case for someone who was recently a D2. On the other hand, sometimes a D3 may have the skill and confidence to do the job but lacks motivation. This is often the case for someone who no longer feels challenged by their work.

D4

Someone is a D4 if they are both highly skilled and highly committed to their job. They have the necessary skills to execute the task and they are both confident and motivated.

Someone brand new to a particular job or task will usually start in D1 and steadily progress to D2, then D3 and finally D4. It’s possible for someone to regress to the previous level too. For example, a D4 might become a D3 again after getting bored and demotivated.

It’s also important to note that a development level is assigned to a person in relation to a specific task or job. Someone might be a D4 in one task but a D1 in another.

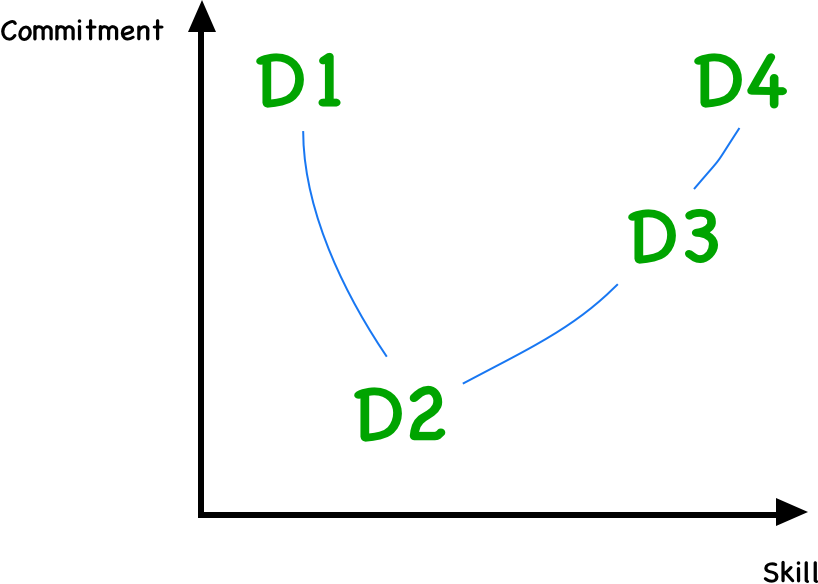

A nice way to think about the development levels is in terms of “skill” and “commitment” (where commitment is defined as a combination of confidence and motivation). We can place the four development levels on a 2d plot, with skill as the horizontal axis and commitment as the vertical axis.

Leadership Styles

A leadership style is defined by how directive you are, and how supportive you are, when interacting with your report.

Being directive means explicitly telling someone what to do, and being supportive means encouraging them.

The lower the skill level of your report, the more directive you should be. And the lower their commitment, the more supportive you should be.

So each of the development levels has a corresponding leadership style.

S1

The S1 leadership style is when you are very directive without being very supportive. You should deploy S1 to manage a D1 who needs a lot of direction due to their lack of skill and context, but doesn’t require much encouragement since they are already highly motivated and eager to learn.

S2

The S2 leadership style is when you are both directive and supportive. You should deploy S2 to manage a D2 who needs some direction due to their lack of experience, and who requires a lot of encouragement as their initial burst of motivation subsides.

S3

The S3 leadership style is when you are supportive without being directive. You should deploy S3 to manage a D3 who doesn’t need much direction since they have all the necessary skills, but they still require some encouragement and confidence-building.

S4

The S4 leadership style is when you are neither directive nor supportive. You should deploy S4 to manage a D4 who is highly skilled, motivated and confident. You don’t need to do much except delegate out the work.

Being directive means telling someone what to do, rather than letting them do what they think is best.

Being supportive means building someone’s motivation and confidence with encouraging words.

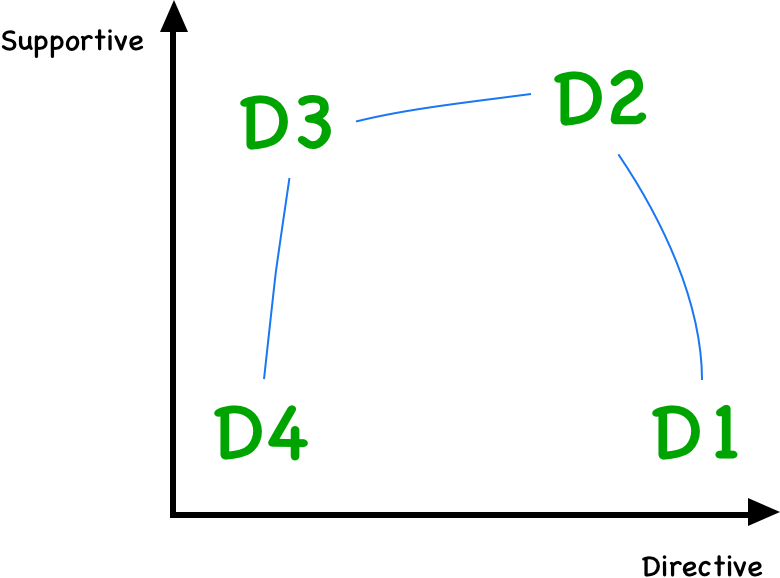

We can place the four leadership styles on a 2d plot, with directive behavior on the horizontal axis and supportive behavior on the vertical axis.

Another way to think about the leadership styles is to pair them with simple phrases that encapsulate the interaction.

S1

“Do it my way.”

There’s no ambiguity here or room for the other person’s ideas. This style is also known as telling.

S2

“Let’s talk about how you do it my way.”

There’s still no ambiguity, but you leave room for the other person’s ideas in the conversation. This style is also known as mentoring.

S3

“Let’s talk about how you do it your way.”

You let them decide the best way to do it, but ask questions, listen to their plan and leave room for your ideas in the conversation. This style is also known as coaching.

S4

“Do it your way.”

You let them decide the best way to do it, and don’t leave any room for your ideas or questions. This style is also known as delegating.

Matching

Matching is the process of assessing someone’s development level and deploying the corresponding leadership style.

The most effective tool for this is a matching conversation. This is where you have an open conversation with someone about their perceived strengths and weaknesses and preferred way of being managed.

However, a conversation can only tell you so much. You need to dig deeper into the activities of your report and get an objective view of their skill level and productivity too. Some degree of domain specific context is necessary to accurately assess development level, and of course to engage in directive behaviour. This is why the path from individual contributor to manager often makes sense.

Common Pitfalls

The most common reasons managers end up doing a bad job are:

- Not properly assessing development level.

- Only being able to use one or two leadership styles.

Not properly assessing development level is usually a result of not having deep enough context on the activities of reports. This is often the case for new or overstretched managers. It is also the result of not having enough matching conversations.

Often managers default to using one or two leadership styles because the others feel unnatural or uncomfortable. I’ve found the most pervasive leadership style at Facebook to be S3, followed by S2. At Facebook, where a lot of value is placed on autonomy and freedom, S1 can feel too bossy and direct. On the other end of the spectrum, S4 can feel a bit lazy, as if you’re not paying enough attention, and aren’t doing your job properly.

But this feeling of discomfort is often just a symptom of not having an open matching conversation. If your report has told you that they want to be hand-held through a task because they are new to it, or if they want to feel completely trusted to do something without you asking questions or offering support, then S1 and S4 feel a lot more comfortable.

Good management, then, is the ability to continuously and accurately assess development levels, and be able to swiftly move between leadership styles to match them.

Most people use one or two leadership styles. Being able to use three puts you into the top 10% of managers. And being able to use all four puts you into the top 1%. This is according to the results of a quiz taken by people who take this class (before the class starts). I took the quiz and came out fairly inflexible with my primary style being S3, and my secondary style being S2. I’d imagine this result is typical for Facebook employees, where the culture of autonomy and coaching is so pervasive.

Examples of Bad Management

All of the times I’ve been managed poorly can be reduced to my manager not following this model.

For example, at one company I worked at, my manager was brand new to management, previously an individual contributor. I clearly remember in the first week of his new role, he was talking to someone about a bug in our codebase. A moment of realization emerged on his face as he turned to me and said:

“Oh I’m a manager now, I get to assign this bug to you.”

His finger pointed at me with a grin. My heart sank a little. I wasn’t sure of why at the time. But looking back, he was using S1 when he should have been using S2 or S3. He took away my sense of autonomy by giving me an explicit instruction to do a simple task with no room for my ideas or input.

Another manager just refused to give me advice on how to lead a project more effectively after they called me out on not doing a good job. Instead they just asked me what I thought the best way was, trying to slowly coax all of the answers out of me. We didn’t make much progress and our meeting finished. They ended the conversation with:

“Let’s keep talking about this next time.”

I walked away feeling a bit lost. Looking back, they were using S3 when they should have used S2. I later heard from others that they felt this way too - that the manager tended to coach rather than mentor, even in situations when mentorship would be more effective.

I asked some friends about their experiences with bad management to check if they could be explained by this model too.

One friend mentioned that his manager tended to micromanage him. He suspected this was because his peer at work was new to the team and so required more directive management but his manager struggled to treat them differently. So he was on the receiving end of S2 instead of S3. This is why being flexible with respect to leadership styles is so important.

Another friend complained that his manager once gave him redundant critical feedback in an area he was already good at. The problem was that his manager didn’t regularly check in on his work, but the one time they did, his performance slipped. So he was subjected to S2 instead of S3. This is why getting deep context on the activities of the people you’re managing is so important.

How To Improve

We ended the class with some concrete, actionable steps to take to become a better manager:

For each person that reports to you, continually assess their development level. If at any point you don’t have enough information to be confident in your assessment, you need to get more data points, have a matching conversation and go a bit deeper. This might require digging into the technical details of the work each person is doing. Bear in mind that someone’s development level can change quickly.

Then, for each person, check if the leadership style you have been using matches their development level. If it doesn’t, adjust it. Be conscious of overusing S2 or S3, but never use S1 or S4 without explicitly agreeing to it in a matching conversation first.

Managing with this model in mind will ensure you avoid those common mistakes that end up making people feel bad about their job. Having a good manager is a key component of people’s happiness and productivity at work. That’s something worth getting right.

Follow @miraan_tabrez