Why You Want to Start a Startup

What Really Drives Entrepreneurs?

I work at Facebook as a software engineer but I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what drives people to start their own startups. I have friends with good jobs at big tech companies that pay extremely well. But they are still obsessed with the idea of doing a startup.

I’d be lying if I said I couldn’t empathize with them. I’ve had side hustles ever since I started secondary school, whether it was freelance web development, dropshipping or affiliate marketing.

While I was at Oxford University, a couple of older grads approached me with their idea to make a social app to connect travelers crossing paths on their trips. It sounded like a cool idea, so we joined forces and started a company.

We built an awesome product, did a lot of marketing and had acquired thousands of monthly active users. Unfortunately, things wound down as we ran out of money, my co-founders wanted to get other jobs and the investors were keen to get tax relief on their “failed” investment.

Soon after that I started another company with a friend — an app to book photographers on-demand. We built an awesome product, did a lot of marketing, acquired repeat paying customers and generated thousands of pounds in revenue. We even got a \$10,000 grant from Y Combinator. But in the end, we both decided that we weren’t passionate enough about the idea to leave our jobs for it. And we weren’t ready to pivot into something completely different.

Although I have a bias towards entrepreneurship, Facebook still feels like a startup. I’m currently working on a brand new machine learning product for advertisers. We’re building something groundbreaking that nobody has done before, with massive potential impact if we are successful. So I’m excited about where we’re headed as a team.

I’ve been trying to identify the key differences between working in a big company like Facebook and building your own startup. My aim is to pinpoint what it is that drives people to leave their highly coveted jobs to go out on their own.

My suspicion was that many of the reasons people give aren’t as good as they seem when you really dig into them.

Michael Seibel, CEO and partner at Y Combinator, writes that:

“there is a certain type of person who only works at their peak capacity when there is no predictable path to follow, the odds of success are low, and they have to take personal responsibility for failure (the opposite of most jobs at a large company).”

The problem with this thesis is that this is exactly what working at Facebook as a (senior) software engineer is like.

Teams and large projects at Facebook spawn up around new ideas for products. These ideas often come from individual engineers. They act as founders, convincing others of their vision, assembling a cross-functional team of other engineers, PMs, designers, UX researchers, content strategists and data scientists. Often there is no predictable path to follow to build the product, and the odds of success are low. If the idea fails, they take personal responsibility for it failing. And since the reward structure at Facebook values impact in the form of successful products built, they are financially motivated to make it a success.

Of course, this is deliberate. Facebook needs to retain their startup culture to get the most out of their entrepreneurial employees — the ones who have massive impact and grow the company.

Money

Money is a big reason people start their own companies, so let’s cover this one first.

Dustin Moskovitz, co-founder of Facebook and Asana, sums up this one nicely. You can view starting a company as one end of a spectrum of risk and reward. The risk is high because you have no information on the performance of the company — its revenue, costs and customers — to make a well informed decision about its likelihood of success. On the other hand, if the company is successful, the reward is high because as a founder you’ll have a large equity stake. Your compensation is all illiquid equity at this stage. But as a founder, you have the power to liquidate the company if you have a willing buyer or are ready to go public.

Moving along the risk spectrum, the next option is to join an early stage startup. You have a bit more information — you may see some early traction and product market fit, and so you can make a better informed decision. This reduces your risk, but also your reward, as you’ll likely get a much smaller equity stake. Your compensation is made up of a low salary and illiquid equity at this stage. And the value of your equity stake could grow 10,000x over the next few years.

This option sounds like the best of both worlds. But often, even if the company is successful, you may not be able to liquidate this equity into cash, as the founders could decide to hold off an exit. This increases your risk. Some companies even reserve the right to buy back your equity for one penny a share if you leave the company, even if the shares have vested. This significantly increases your risk.

This spectrum continues right up to the option to join a big public tech company as employee number 50,000. Your risk is extremely low as the company is no longer a startup. It has found product market fit, it has scaled up its operations, and it is generating a healthy profit year after year. Your compensation is made up of a high salary and a large liquid equity package at this stage. This makes your risk very low. However, the company probably won’t grow 1000x over the next 8 years, which limits the growth of your equity. It might grow 3–4x though.

Another factor to bear in mind is that when your wealth is tied up in illiquid assets like equity in a startup, you can’t invest it in other opportunities that come your way.

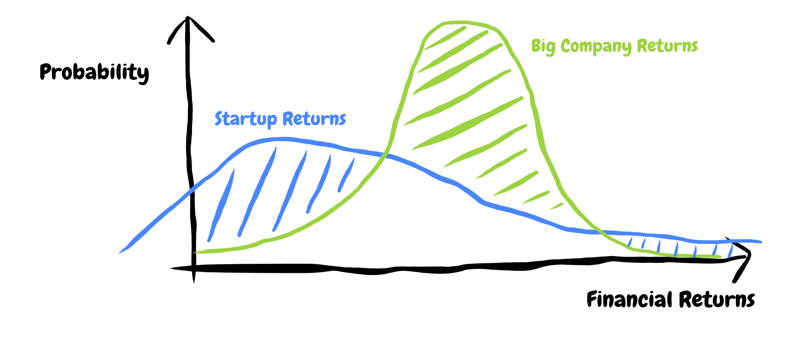

In general, you can view different points of this spectrum as representing a different probability distribution of possible financial returns. The means of the distributions — your “expected returns” — get progressively higher as you move along the spectrum. But the distribution also gets narrower. This means that on average you’ll make more money in a big tech company, but you’re more likely to get extremely large financial returns in a startup compared to a big company.

But still, some people fancy themselves to be in the top 1% that will be likely to make more money in a startup than a big company. Big tech companies know this, and so have accounted for it in their reward structures. If you really are this good, you will continue to get promotions and increase your total compensation. Top engineers have pay packages in excess of \$1m / year.

If you do the maths, the median “successful” scenario for an ambitious engineer is not wildly different when you compare working in a big company vs. starting your own company.

Extracting the Fruits of Your Labour

Some people just don’t like the idea of making someone else richer. By working at a big company, you’re just making the founders more wealthy, and only taking a slice of the value you’re creating for yourself.

But the same is true if you start a startup. You’ll have some investors who you’ll be working to make richer, and since your equity stake is < 100%, you’ll never fully extract all of the value you create for yourself.

Another related point people make about doing your own startup is that you can condense 3 years of work into 6 months, by driving yourself harder than you thought possible. In a startup, if you work on the right things, you can reap 3 year’s worth of value for yourself after those 6 hard months. But in a big company, it’s said that you don’t have this option — if you decide to do 3 year’s worth of work in 6 months, you don’t get rewarded in proportion.

However, it’s not unheard of for people at Facebook and other big tech companies to get disproportionately rewarded, compared to others, for going above and beyond. Whether it’s via rapid promotions or large discretionary equity payouts, choosing the pace at which you work and extracting proportionate rewards is possible in a big company.

Excitement

People often find the idea of starting their own company more exciting. This makes sense as taking risks can be exciting. But then, they wouldn’t get the same kick out of going to the casino. It’s a different kind of excitement — the excitement of building something new, with no idea of whether or not it’s going to work.

I’ve had this excitement working at Facebook too. For some products, we’re simply playing catch up by building products that our competitors or partners have already built. But for other products, they really are groundbreaking new ideas, sometimes powered by novel technology, which we get to build. And we have no idea of whether it’s going to work. But if it does, the potential impact can be huge.

Freedom and Travel

People cite “freedom” as another reason to go out on their own. They can work when they want, travel when they want and rest when they want.

This is often the case for a lifestyle business, but if you are aiming to create a business worth $100mn or $1bn, you can say goodbye to this kind of freedom.

Besides, in a big company, working hours can be extremely flexible, and people often work from home. Travel to other offices is encouraged and policies are very generous. For longer trips, you get business class flight upgrades and always stay at nice hotels.

Ownership

In my view, the single biggest thing that people crave in their work is ownership. Ownership is when you take complete personal responsibility and accountability for the success of your project. You are the one driving things forward, shaping direction, coming up with new ideas, taking initiative, getting others onboard and generally maintaining awareness of all aspects of the project. You actively seek out the blind spots of the team, making sure nothing has been forgotten or missed, and you instantly jump in to resolve problems when they arise.

Ownership and leadership can both be thought of as filling the vacuum. You put forward ideas because nobody else has. You draw attention to issues because nobody else has. You jump in to fix problems because nobody else has. You do everything which everyone else has missed, and consequently keep the team and project on track, while acting as a last line of defense.

This mode of behavior is the main delta between a mid-level engineer and a senior engineer at Facebook. The reason it’s sometimes challenging for mid-level engineers to successfully take ownership of projects is that if they drop the ball, even temporarily, a senior engineer might just fill the vacuum themselves. Once ownership is effectively given away like this, it’s hard to take back.

Taking ownership of a product requires a certain amount of care and emotional investment. This leads to pride and joy when your product grows and succeeds. This is what people find so fulfilling.

At a startup, you’re forced to take ownership, because there is nobody else to fill the vacuum. This is why less experienced employees might often find startups much more fulfilling than their big company jobs.

Autonomy

As well as ownership, entrepreneurial people deeply crave autonomy. Indeed, autonomy is often what allows them to invest in a product to care about it deeply enough to take ownership of it. In a startup, you have a large degree of autonomy over what you do and how you do it. Nobody can tell you what to work on — it’s up to you decide what the best thing to work on is.

The same is true if you are an engineer at Facebook or other big tech companies. Nobody can force you to work on something in particular. It’s up to you to decide what will be impactful. You can heed the advice of others on your team and let yourself be influenced by them. But nobody exercises any authority over you.

One criticism of big company culture is the need for approvals from leadership and the politics involved in getting the green light to work on things. This definitely happens, but it’s necessary to make sure people don’t waste resources by building products that won’t be impactful. In just the same way that startup founders need to convince investors and other stakeholders of their proposed direction, engineers and product managers need to convince company leadership of theirs.

Growth Multipliers

Another reason I’ve heard for doing a startup is that it’s more fulfilling to go from 0 to 1, rather than 1 to n. You’d rather help a small company grow 100x than help a big company grow 2x.

I can see this — there’s something amazing about building something up from nothing. But then, this is what happens within big companies all the time. Ideas, products and teams spawn from nothing and go from 0 to 1.

I’ve noticed that the best teams at Facebook often function like a startup. People are driven towards a common cause, unite together and work hard to achieve their goals. There’s a great sense of camaraderie and shared ambition.

Wearing Many Hats

Another common reason people give for wanting to do a startup is that it’s the only thing which sufficiently pushes them to expand their skill set in such a wide variety of domains. As a startup founder, you’ll have to switch between engineering, product management, design, sales, marketing, fundraising, people management and public speaking.

Some people thrive off the challenge of being required to excel in so many diverse fields — all in the name of doing whatever it takes to get their startup off the ground.

But then, this is exactly what senior engineers and managers at Facebook end up doing too. They require a strong grasp of all the cross functional disciplines of the people they work with — designers, content strategists, product managers, UX researchers and product marketing managers (who are part of sales). They also do whatever it takes to set their products up for success — because they have taken ownership.

Passion

In my opinion, the best reason for someone to start a company is that they are passionate about solving a problem that either they have or people they know have.

Passion for the problem you’re solving is what will get you through the tough times that lay ahead as you struggle to make your startup a success. It can keep you motivated when you feel like quitting. It brings meaning and purpose to your work.

It also makes it more likely that the problem you are solving is real and worth solving. Far too often, people pursue startups because they sound like good ideas. These are the kind of ideas people jot down in their “ideas list”. I’m a big fan of Michael Seibel’s advice to keep a “problems list” rather than an “ideas list”. You’ll usually only be passionate about a problem that affects you or people you know, so passion can be great early validation for your problem.

If you deeply care about solving a problem, and a big company is not the right place to be to do so, then this is a great reason to go out on your own.

Self Expression

Related to the last two points, I think a big part of founders’ desires to start companies is their need for self expression. Working in a big company requires you to work on things that align with the company’s mission, values and priorities. When this aligns with what matters to you, you feel fulfilled, and your work can be a form of self expression.

Indeed, software engineering sometimes feels like an art. Programmers get a great deal of fulfillment from writing code and building products. The process of creating something and releasing it out into the world for others to interact with is a high that many of us seek.

I think Facebook does a great job of encouraging self expression through work. New joiners get to pick their teams, and you get the chance to try out new teams and switch to them permanently if you think you’d be happier there. This is not common practice in other big companies, but I think it’s a great system worth adopting everywhere.

To Conclude

Many aspects of entrepreneurship that people crave can be found in a big company. Admittedly, Facebook has heavily engineered its internal structure to retain its startup environment and culture. This is what enables them to retain ambitious, entrepreneurial people who would otherwise do their own startups.

At a certain level, there’s not much difference between building new products in a big company and your own startup.

That being said, the best reason to start a startup is to solve a problem you’re passionate about. Passion leads to excitement, ownership and the motivation to stick it out when it gets tough. It also makes it more likely that the problem you’re solving is real and big enough.